LOS LECTORES DEBEN SER CONSCIENTES DE QUE ESTA ENTRADA COTIENE ALGUNAS IMÁGENES QUE PUEDEN RESULTAR DESAGRADABLES

READERS SHOULD BE AWARE THAT THIS POST CONTAINS SOME IMAGES THAT SOME MAY FIND DISTURBING

El catálogo que tengo en mis manos se llama: La vanguardia China: veinte años de arte contemporáneo chino, una recopilación maravillosa de obras de diferentes artistas. Acompañó la exposición que llevó el mismo título en 2008, organizado por una serie de museos y centros de arte de Japón para popularizar el arte chino y fue expuesta en el Centro Nacional de Arte de Tokio, el Museo Nacional de Arte de Osaka y Aichi Museo Prefectoral de Arte de Nagoya. Encontré libro caminando por las calles de Barcelona, alguien lo dejó en la acerca donde me encontró a mí, así que hoy quiero compartir unas partes selectas con vosotros.

The catalogue I’m holding in my hands is called: Avant-garde China: Twenty years of Chinese Contemporary Art, a wonderful compilation of works by many different artists. It accompanied the exhibition bearing the same title in 2008 organized by a number of museums and art centres in Japan to popularize Chinese art and was exhibited in The National Art Center in Tokyo, The National Museum of Art in Osaka and Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art in Nagoya. I found the book left behind on the pavement for the right person to come along and claim it as I was walking around in the streets of Barcelona, and the right person seems to have been me, so today I wish to share it with you, part of it that is.

Aunque el término vanguardia despierta recuerdos del pasado en el occidente, no hay que olvidar que la exposición china al arte desde fuera de sus fronteras, y especialmente al arte occidental, empezó de nuevo hace relativamente poco tiempo. Las Estrellas (Xingxing) Grupo de Beijing se cree que iniciaron este movimiento. Les mencioné antes en relación con el artista conceptual de fama mundial Ai Weiwei, que era un miembro del grupo que hizo lo impensable – un llamamiento a la libertad de expresión – y en sus primera exposición pública al aire libre, incluyeron algunas obras que tuvieron mucha semejanza con las obras de artistas occidentales de principios del siglo veinte. Había una conexión directa entre el arte chino y la vanguardia occidental en la década de 1930. Pang Xunqin fundó la Sociedad de la tormenta en Shanghái, a su regreso de París, esta misma dio lugar más tarde al Modernismo Shanghái y la formación de varias sociedades de arte modernista pero esos movimientos fueron reprimidos por la República Popular de China y, posteriormente, la Revolución Cultural China (1966-1977).

Whereas the term avant-garde awakens memories of the past in the occident, one must not forget that Chinese exposure to art from outside its borders, and more importantly western art, restarted relatively recently. The Stars (Xingxing) Group of Beijing are believed to have initiated this movement. I mentioned them before in connection with the world-famous conceptual artist Ai Weiwei, who was a member of the group that did the unthinkable – appealed for freedom of expression – and on their first public outdoor exhibition, they included some works that bore resemblance to early western artists’ works. There had been a direct connection between Chinese art and the western avant-garde in the 1930s, when Pang Xinquin founded the Storm Society in Shanghai on returning from Paris, which then led to Shanghai Modernism and the formation of various modernist art societies but those movements were stifled by the People’s Republic of China and subsequently the Cultural Revolution (1966-1977).

Aunque también se suprimió el movimiento de las Estrellas, no había manera de que China pueda evitar la influencia occidental por más tiempo, por lo que el gobierno hizo la vista gorda y se mantuvo en silencio, tanto que en 1985 se llevó a cabo una exposición de Robert Rauschenberg en Pekín y Lhasa; y con los años cada vez más, la influencia occidental impregnó la escena del arte chino. Pero mientras que nuestra evolución artística ha sido constante e ininterrumpida, los artistas chinos se transformaron en un par de décadas, y lo hicieron de una manera brillante. Imaginémonos mezclar la obra de Marcel Duchamp, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol y Jeff Koons sin tener en cuenta la secuencia de tiempo e ignorando las diferenciaciones entre los distintos movimientos artísticos y sus inspiraciones. No obstante, este enfoque concedió a los chinos una libertad de mezclar estilos y adaptarlos a sus propias situaciones sin restricciones conceptuales. Esta nueva exposición dio lugar a la creación de varios grupos de vanguardia en la década de 1980. Echemos un vistazo a cuatro artistas que empezaron a trabajar durante este período.

Though the Stars movement was also supressed, there was no way for China to prevent Western influence any longer, so the government turned a blind eye to it and kept silent, so much so that in 1985 a Robert Rauschenberg exhibition was held in Beijing and Lhasa; and over the years more and more western influence permeated the Chinese art scene. But whereas our artistic evolution has been constant and uninterrupted, Chinese artists transformed themselves in a couple of decades, and they did it brilliantly. Imagine mixing the work of Marcel Duchamp, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol and Jeff Koons with no regard to time sequence and ignoring the differentiations between the various art movements and their inspirations. However, this approach granted the Chinese a freedom to mix styles and adapt them to their own situation with no conceptual restraints. This new exposure resulted in the establishment of various avant-garde groups in the mid-1980s producing several radical groups. Let’s look at four artists who started working during this period.

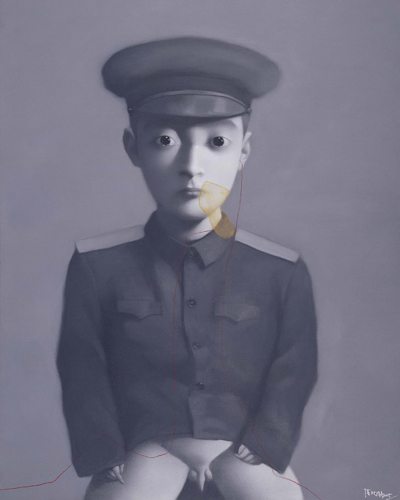

Zhang Xiaogang

Nacido en Kunming, provincia de Yunnan, en 1958, Zhang fue testigo directo de la turbulencia de la Gran Revolución Cultural que se refleja en sus cuadros sombríos. Estudió arte en la Academia de Bellas Artes de Sichuan y se ha convertido en uno de los pintores más prestigiosos de China.

Born in Kunming, Yunnan Province, in 1958, Zhang witnessed first-hand the turbulence of the Great Cultural Revolution and reflected it in his sombre paintings. He studied art at the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts and has become one of China’s most highly regarded painters.

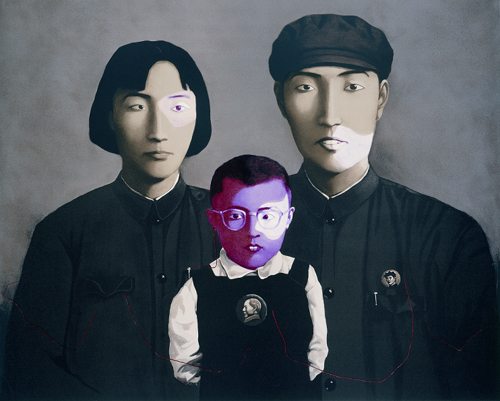

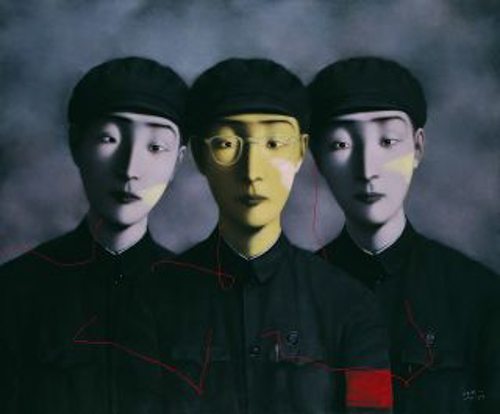

En 1993, al encontrar algunos viejas fotos de la familia, comenzó su serie The Bloodline: Big Family (Línea de sangre: Familia Grande), que se basa en retratos de familia populares de los años 60 y 70 tomadas en estudios de fotografía chinos. Estas pinturas, inspiradas por fotos utilizadas anteriormente como elementos decorativos, carecen de cualquier sentimentalismo o romanticismo; en cambio, representan a personas melancólicas que han resignado a cadena cultural y social. Zhang encontró una manera hábil para combinar representaciones de retratos casi planos que dan una sensación de esterilidad con la vida representada en el uso de colores vivos, aunque las aplica de modo escaso.

In 1993 upon finding some old family paintings, he started his series The Bloodline: Big Family, which is based on popular family portraits of the 60s and 70s taken in Chinese photography studios. These paintings, inspired by images formerly used as decorative items, are lacking in any sentimentality or romanticism; instead, they portray melancholic people who have resigned themselves to cultural and social imprisonment. Zhang found an adroit way to combine almost plain representations of portraits that give a sensation of sterility with life represented in the use of bold colours, albeit scarce application of them.

Durante la Revolución Cultural, el término «familia» se aplicaba no sólo a la unidad más pequeña de la sociedad, sino también al conjunto de la propia China, y su líder totalitario Mao Zedong fue representado como su padre. Las líneas rojas en las pinturas que conectan a la gente no sólo aluden a la línea de sangre que los une, sino a «cadenas que las contienen en la oscuridad».

During the Cultural Revolution, the term “family” was applied not only to the smallest unit of society, but also to the whole of China itself, and to their totalitarian leader Mao Zedong was denoted as its father. The red lines in the paintings that connect the people do not only allude to the bloodline that connects them but to “chains that restrain them in the darkness”.

«Una fotografía no es simplemente un registro de lo que está delante de la lente de la cámara. También expresa el deseo de la gente hacia el futuro y enfatiza las desgracias por venir.»

“A photograph is not simply a record of what stands before the camera lens. It also expresses people’s desire for the future and hints at misfortunes to come.”

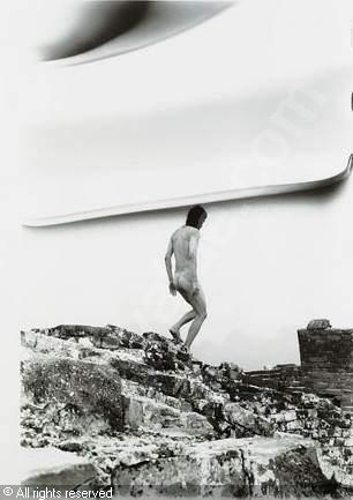

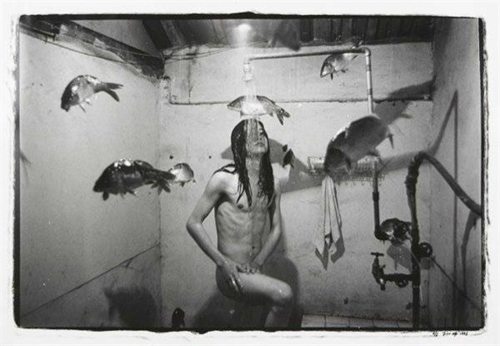

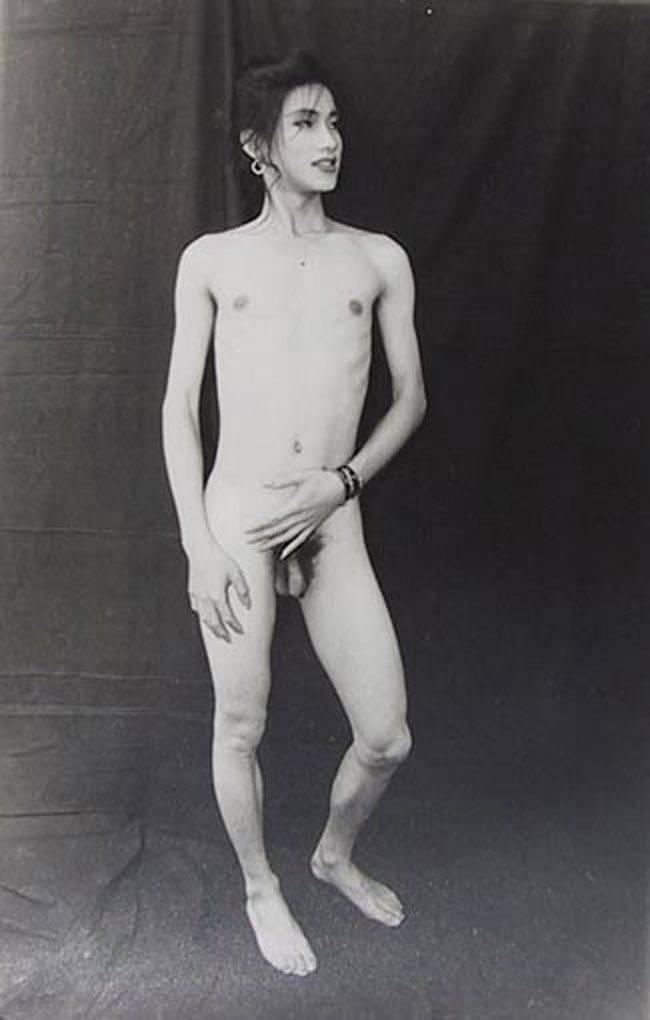

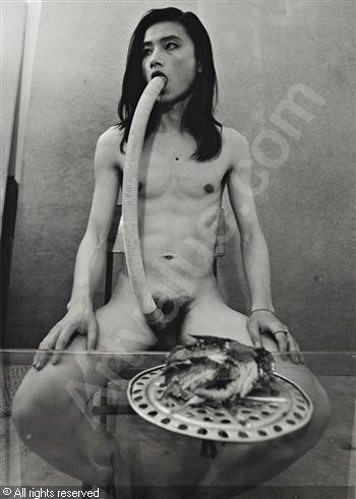

Ma Liuming

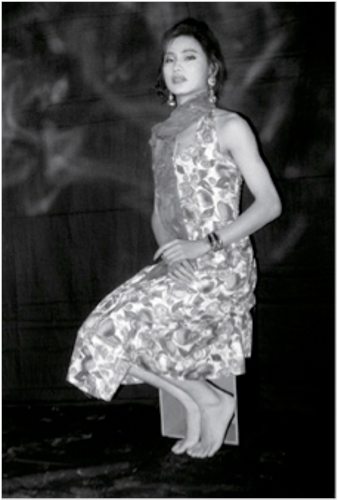

Ma estudió pintura al óleo en la Academia de Bellas Artes de Hubei, en su ciudad natal, pero se convirtió en una artista de «performance», creando así un alter ego que Ma llama Feng-Ma Liuming. Feng es un nombre femenino y un homónimo con otra palabra que significa separación. No fue por casualidad que Ma eligió este nombre en particular; quería crear una separación entre él y el personaje imaginario en que se transforma en sus actuaciones.

Ma studied oil painting at the Hubei Academy of Fine Arts, in his hometown, but he went on to become a performance artist, creating an alter ego who Ma calls Feng-Ma Liuming. Feng is a female name and a homonym with another word that means separation. It was not by chance that Ma chose this particular name; he wanted to create a separation between himself and the imaginary character he transforms into in his performances.

Con la creación del Feng-Ma, encontró una manera ingeniosa de trascender «categorías físicas y sociales de género». Muchas de las imágenes que capturan elementos de sus actuaciones parecen perversas, por ejemplo de la serie Lunch (Comida), pero también cuestionan los valores y las restricciones a la libertad de expresión impuesta a los artistas y las personas por un gobierno autoritario.

With the creation of Feng-Ma, he found an ingenious way of transcending “physical and social categories of gender”. Many of the images that capture elements of his performances come across as perverse, for example the Lunch series, but they also question conventional values and restrictions of freedom of expression imposed upon artists and people alike by an authoritarian government.

Peng Yu & Sun Yuan

Aunque los dos artistas se graduaron de la Facultad de Pintura de la Academia Central de Bellas Artes de China en Beijing, los dos se sintieron atraídos por las instalaciones y el “performance” más que la pintura tradicional y debido a sus similitudes en sus temáticas comenzaron a colaborar en 2000.

Although the two artists graduated from the Painting Faculty of the China Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, they were drawn to installations and performance more than traditional painting and due to similarities in their subject matter they began to collaborate in 2000. Sun Yuan’s installation Herdsman (1998) makes use of 200 bloody backbones of goats that are scattered around a snowy background, creating a surreal and dystopian image that resembles a world of a horror movie.

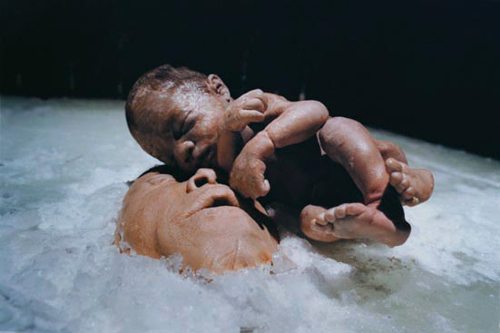

Con su siguiente instalación Honey (miel)(1999), va aún más allá al mostrar los cadáveres de un hombre y un bebé. Sólo la cabeza del hombre es visible, el resto del cuerpo está cubierto de hielo y el bebé se coloca sobre él cubriendo la mitad de la cara del hombre. La imagen es muy perturbadora, aún más porque es una imagen espantosa de la vida que está condenada inevitablemente.

With her next installation Honey (1999), she goes even further by exhibiting the cadavers of a man and a baby. Only the head of the man is visible, the rest of the body is covered in ice and the baby is placed over him half covering the man’s face. The image is deeply disturbing, even more so because it is a gruesome picture of life that is inevitably doomed.

La instalación Curtain (Cortina) (1999) de Peng Yu consistió en una pared llena de pequeños animales vivos «como langostas (400 kg), ranas toros (30 kg), serpientes (30 kg) y las anguilas (20 kg) … unido a unos cables de acero» y expuestas como si fuesen parte de una cortina.

Peng Yu’s installation Curtain (1999) consisted of a wall full of small living animals “such as lobsters (400 kg), bullfrogs (30 kg), snakes (30 kg) and eels (20 kg) … attached to steel wires” and displayed resembling a curtain.

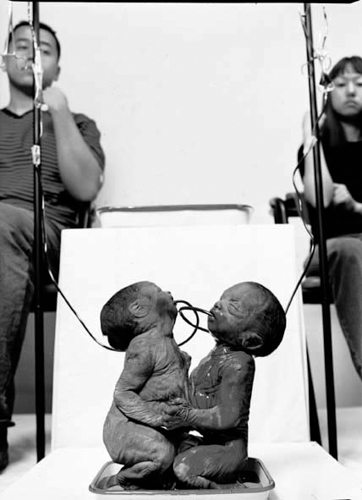

Uno de los primeros frutos de la colaboración entre los dos artistas es Body Link (Enlace de Cuerpo), basado en la idea del renacimiento y la resurrección de Cristo. En la pieza de performance, los cuerpos de dos bebés están unidos y los artistas transmiten su sangre en ellos. El dúo también es conocido como el «grupo de cadáver» por su uso recurrente de los cadáveres y los huesos, lo que da a las obras un carácter macabro.

One of the first fruits of their collaboration is Body Link, based on the idea of rebirth and the resurrection of Christ. In the performance piece, the bodies of two babies are bound together and the artists streamed their blood into them. The duo is also known as the “corpse group” because of their reoccurring use of corpses and bones, which yields the work a macabre character.

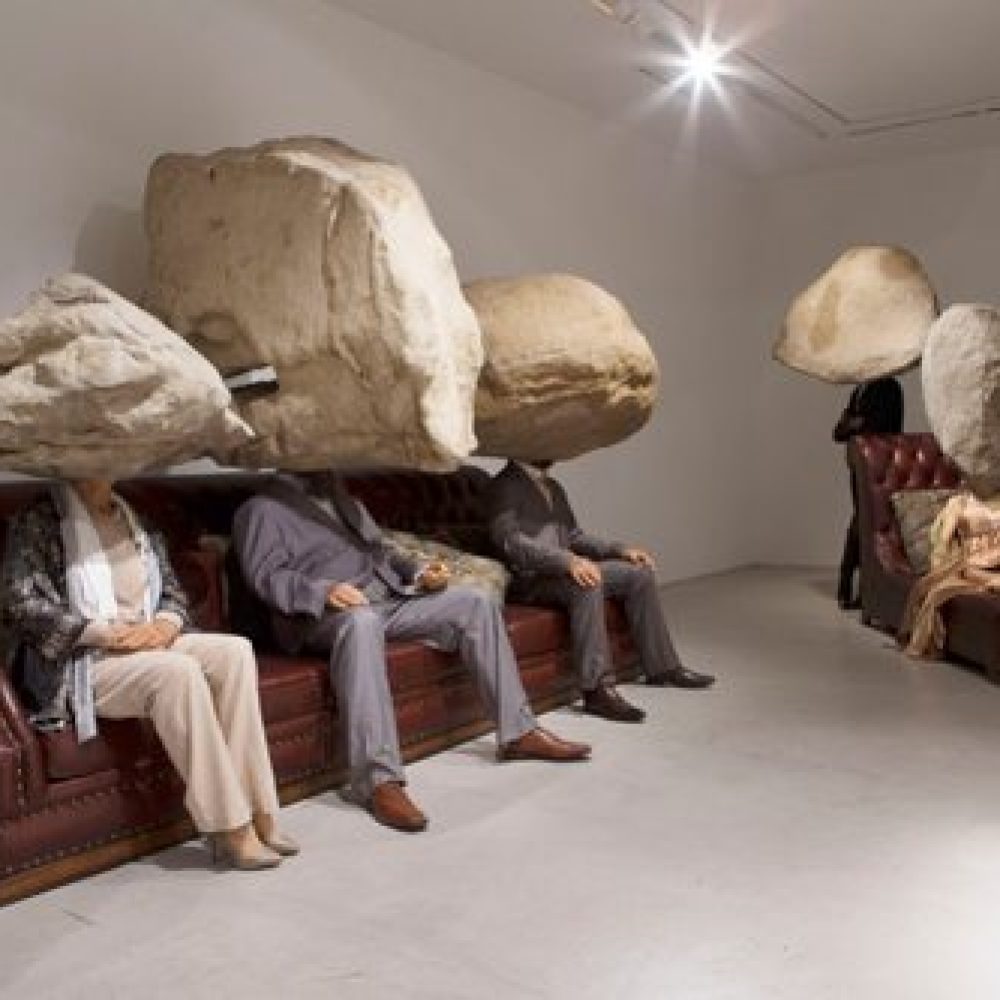

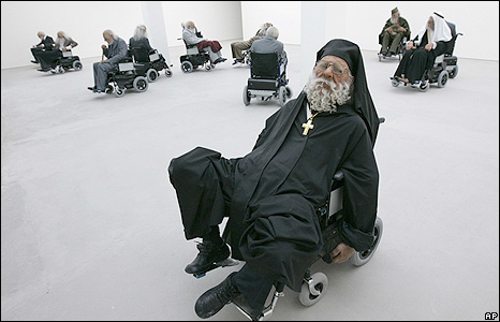

Su instalación, Old Person’s Home (Hogar de anciano) se compone de trece esculturas de ancianos vestidos con trajes étnicos y sentados en sillas de ruedas eléctricas vagando libremente en el espacio expositivo, una vez más, en alusión a la característica más fundamental de la vida: tiene un fin y como nos acercamos a ella, somos desesperadamente iguales.

Their installation, Old Person’s Home consists of thirteen sculptures of old people dressed in ethnic costumes and seated in electric wheelchairs roaming around freely in the exhibition space, yet again alluding to the most fundamental feature of life: it has an end and as we approach it, we are desperately equal.

Explorando el arte de otras culturas puede ser especialmente gratificante, aún más si eres sensible a los matices que son los componentes básicos de la cultura actual. En el camino, puede que te encuentres preguntándose acerca de las cosas que previamente habías tomado por sentado y podrías incluso llegar tan lejos como para ver a tu propia cultura y a ti mismo con nuevos ojos.

Exploring the art of other cultures can be especially gratifying, even more so if you are sensitive to the nuances that are the building blocks of the actual culture. Along the way, you might find yourself wondering about things that you have previously taken for granted and you could even go so far as to see your own culture and yourself with fresh eyes.