En septiembre, al inicio del curso de fotografía avanzada, José Luis nos dió la tarea de tomar una foto de una manzana. Por lo que nos vimos obligados a centrarnos en un conjunto muy limitado de elementos: la manzana, la luz y la sombra. Sólo al ver los resultados pudo ser claro para todos nosotros, que a pesar de las limitaciones, las imágenes eran muy diferentes, cada una de ellas reflejaba algo de lo que somos y cómo percibimos nuestro entorno. De hecho, es imposible no revelar algo de tu personalidad en tu producción artística.

In September, at the beginning of the advanced photography course, we were given the task of taking a picture of an apple. Through this introductory homework, we were obliged to focus on a very limited set of elements: the apple, light and shadow. Only upon looking at the results did it become clear to all of us, that despite the limitations, the images were very different, each one of them reflecting something of who we are and how we perceive our environment. Indeed, it is impossible not to disclose something of your personality in your artistic output.

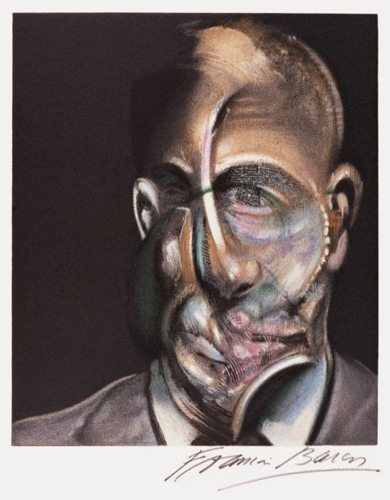

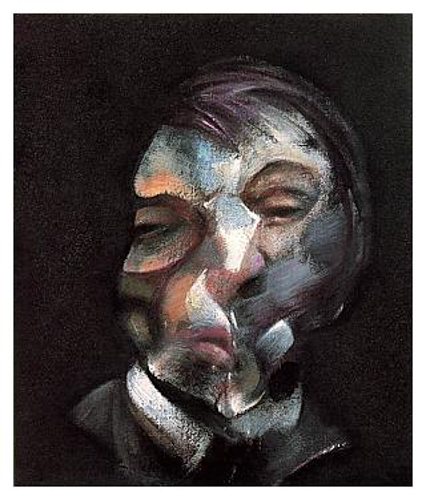

Mi manzana era algo entre una mancha y una sucesión de manzanas contra un lienzo. El resultado no ha sido un éxito, pero al instante quedó claro lo que realmente me interesaba: la presentación del tema en movimiento constante – algo que yo había visto en la obra de uno de los gran maestros nacidos en Irlanda del siglo XX, Francis Bacon, el pintor que ha encontrado un puente perfecto entre la pintura abstracta y figurativa representando sus sujetos como si fueron en cuatro dimensiones y fluidos – evitando la crudeza del cubismo.

My apple was something between a smudge and a succession of apples against a canvas. The result was nothing much, but it instantly became clear what actually interested me: presenting the subject in constant movement – something that I had seen in the work of one of the Irish-born masters of the twentieth century, Francis Bacon, the painter who found a perfect bridge between abstract and figurative painting by depicting his subjects as if in four dimensions and yet still flowing – and without the crudeness of cubism.

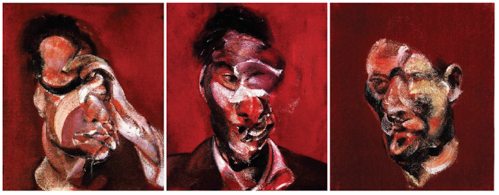

Francis Bacon tenía una personalidad muy interesante que es inmediatamente evidente en sus representaciones de la gente, por lo general en lugares aislados; las pinturas contienen apenas más que el retrato en sí y un telón de fondo plano cuidadosamente construido con sólo un par de colores. El trabajo elaborado de los sujetos, especialmente sus caras – presentados como si estuvieran en movimiento, está maravillosamente complementado por el fondo tenue y plano, llamando así la atención del espectador al único elemento esencial en la pintura: la persona. Su trabajo también destacó los tres elementos: el sujeto, la luz y la sombra, pero en su caso el medio habilitado transmutaciones distintas de los de la fotografía.

Francis Bacon had a very interesting persona that instantly comes through in his depictions of people, typically in isolated settings; the paintings contain hardly anything other than the portrait itself and a flat backdrop carefully constructed from only a couple of colours. The elaborate work on the subjects, especially their faces – presented as if in movement, is wonderfully complemented by the subdued, flat background, thereby drawing the viewer’s attention to the only essential element in the painting: the subject. His work also emphasised those three elements: subject, light and shadow, but in his case the medium enabled transmutations unlike those of photography.

No creo que sea necesario saber nada de un artista que aprecia su trabajo, ya sea si el trabajo resuena contigo o no. Propio Bacon dijo que no había nada que entender en un cuadro, que tenía que ser sentido y permitir a la pintura que desbloque cosas en el espectador; sin embargo, al ver su vida y algunas de sus obras más emblemáticas, podríamos obtener una mayor apreciación de la personalidad detrás de su conjunto de imágenes provocativo y muy inquietante.

I don’t believe it is necessary to know anything about an artist to appreciate their work, either the work resonates with you or it doesn’t. Bacon himself said that there was nothing to be understood in a painting, it had to be felt and allowed to unlocked things in the viewer; nonetheless, by looking at his life and some of his most iconic works, we might gain a greater appreciation of the personality behind his provocative and highly disturbing set of images.

Bacon nació en 1909, destinado a una vida de muchas dificultades, y no sólo, porque tenía que vivir a través de los horrores de las dos guerras mundiales: él también era homosexual. Por otro lado, tenía una mente brillante, y una determinación para tener éxito en lo que él eligió para llevar a cabo, ignorando cualquier norma social y expectativa. Pero no fue hasta 1927, al ver una exposición de Picasso en París, que él finalmente vio las posibilidades inherentes a la pintura que le excitaban; sólo entonces decidió tomarla como una profesión, aunque no dedicó a ella por completo durante muchos años más.

Bacon was born in 1909, destined for a life of many hardships, and not merely, because he had to live through the horrors of the two world wars: he was also homosexual. On the other hand, he had a brilliant mind, and a determination to succeed at what he chose to accomplish, disregarding any social norms and expectations. But it wasn’t until 1927, upon seeing a Picasso exhibition in Paris, that he finally saw the possibilities inherent in painting that excited him; only then did he decide to take it up as a profession, although he didn’t dedicate himself to it totally for many years.

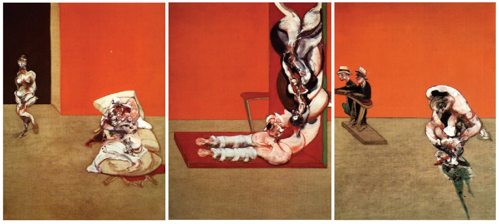

Crucifixión/Crucifixion

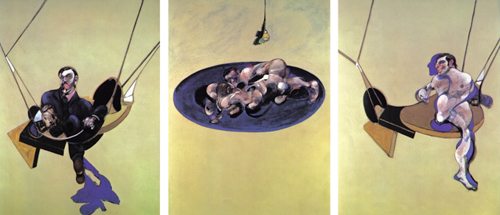

Tres estudios para figuras en la base de una crucifixión, 1944 es probablemente una de las obras más emblemáticas de Bacon. El pintor trató de captar el estado de ánimo de la crucifixión en lugar de representar lo que podría haber sucedido. Su representación habla a nuestros sentimientos y miedos profundamente arraigados; que representa el sufrimiento y el dolor en lugar de pintar hermosos cuerpos medio desnudos románticos pintarrajeados con éxtasis falso.Terminó el tríptico en quince días, pintando mientras bebia y bajo la resaca; la mayoría de las veces ni siquiera sabía lo que estaba haciendo. Posteriormente Bacon creía que estar intoxicado lo liberó, y era lo que realmente hizo que el proyecto fuese posible de ejecutar.

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, 1944 is probably one of Bacon’s most iconic works. The painter tried to capture the mood of the crucifixion as opposed to depicting what might have happened. His representation speaks to our feelings and deep-rooted fears; it depicts suffering and pain as opposed to romanticised half-naked beautiful bodies daubed with faux ecstasy. He finished the triptych in a fortnight, painting while drinking and under hangovers; most of the time he didn’t even know what he was doing. Bacon subsequently believed that being intoxicated freed him, which made the project be possible to execute.

As a self-proclaimed atheist, crucifixion had a very different meaning for Bacon: he saw it as one man’s act of violence towards another. The result was shocking: people wanted to forget about the horrors of war and start anew, and the image of erotically distorted meat-like figures with screaming mouths revolving on the canvas was not one they wanted to see.

El Acorazado Potemkin/Battleship Potemkin

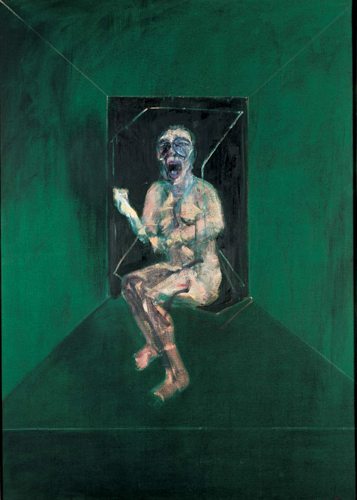

Las fotografías fueron una parte esencial de la vida de Bacon; se rodeó de ellas y las utilizó como fuente de inspiración. Estudio para la enfermera en el Acorazado Potemkin (1957) se basa en un fotograma tomado de la película El acorazado Potemkin dirigida por Eisenstein.

Photographs were an essential part of Bacon’s life; he surrounded himself with them and used them as a source of inspiration. Study for the Nurse in the Battleship Potemkin (1957) is based on a still taken from the film Battleship Potemkin directed by Eisenstein.

Al ver una imagen, ya sea en una película, en un periódico o en cualquier otro lugar, la imaginación de Bacon se movía y transmutaba estas imágenes, llevándolas a los extremos. La enfermera aparece desnuda, aislada y encerrada en el lienzo sin nada a su alrededor, excepto unas pocas líneas semejantes a una jaula de cristal, como si fuera atrapada en el inconsciente del pintor donde no hay nada más que el miedo y la soledad.

Upon seeing an image, whether in a film, newspaper or anywhere else, Bacon’s imagination shifted and transmuted these images, taking them to extremes. The nurse is featured naked, isolated and locked into the canvas with nothing around her except a few lines resembling a glass cage, as if trapped in the unconscious of the painter where there is nothing but fear and loneliness.

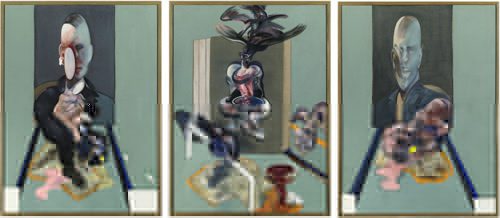

Velázquez y el Papa Inocencio X/Velázquez and Pope Innocent X

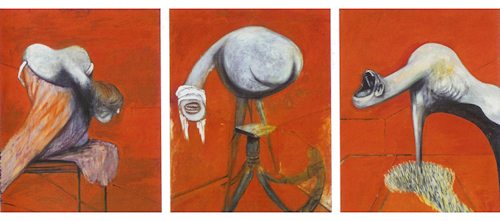

Aunque Bacon nunca vio la pintura original del Papa Inocencio X por Velázquez, parecía haber sido fascinado por la imagen. Su reinterpretación del mismo es una imagen cruda y siniestra que evoca ideas de infierno, la muerte en la silla eléctrica y el sufrimiento en general; no es la imagen benevolente generalmente transmitida por figuras religiosas.

Although Bacon never saw the original painting of Pope Innocent X by Velazquez, he seemed to have been fascinated by the images. His reinterpretation of it is a crude and sinister image that evokes ideas of hell, death in the electric chair and suffering in general; it is not the benevolent image usually conveyed by religious figures.

Bacon fue fascinado por las pinturas de Velázquez porque aunque son figurativas y realistas hasta el punto de convertirse en ilustraciones, él tuvo la magnífica potencia para desbloquear el más profundo de los sentimientos con sus pinturas: no sólo pintó la apariencia de una persona, él era un maestro de emociones y las atrapó en su lienzo con brillantez. Bacon llevó todo a un paso más allá; a través de su estilo idiosincrásico, distorsionó la imagen del Papa en algo más cerca de su propio estado interno.Bacon argumentó que mientras que a Velázquez se le exigió la tarea de inmortalizar sus sujetos, gracias a la fotografía pintores estaban ahora relevados de esta responsabilidad y podrían centrarse en la representación de los estados mentales y emociones en su lugar.

Bacon was fascinated by Velazquez’s paintings because although they are figurative and realistic to the point of becoming illustrations, he had the magnificent power to unlock the deepest of feelings with them: he did not only paint the appearance of a person, he was a master of emotions and caught them on his canvas brilliantly. Bacon took this a step further; through his idiosyncratic style, he distorted the image of the Pope into something that closer to his own inner state. Bacon argued that whereas Velazquez was entrusted with the task of immortalising his subjects, thanks to photography painters were now relieved of this responsibility and could now focus on representing mental states and emotions instead.

No sólo fue liberado de la representación, sino de creencias religiosas también. Mientras Velázquez podría haber sido limitado por la creencia de considerar solamente la significación religiosa, Bacon vio lo que muchos de los intelectuales de su época: el hombre como un ser inútil que tiene conciencia de su mortalidad y no tiene esperanza de una vida de ultratumba.

Not only was he freed from representation, but from religious beliefs as well. Whereas Velazquez might have been constrained by belief to only consider religious signification, Bacon saw what many of the intellectuals of his age did: man as a futile being conscious of mortality and without hope of an afterlife.

His influence

No sólo fue liberado de la representación, sino de creencias religiosas también. Mientras Velázquez podría haber sido limitado por la creencia de considerar solamente la significación religiosa, Bacon vio lo que muchos de los intelectuales de su época: el hombre como un ser inútil que tiene conciencia de su mortalidad y no tiene esperanza de una vida de ultratumba.

The mood Bacon captured was that of his unquiet time, where the possibility of disaster was ever present. He developed an acute obsession with death and the darker side of life. He believed that life had no meaning –a thought put forward by philosophers such as Sartre – and he believed in giving life meaning through doing, which, in his case, meant painting.

Bacon ha influido a toda una generación de pintores a través de su filosofía de vida y de sus pinturas, una de esos pintores es Damien Hirst, quien también trató la muerte como sujeto artístico – en su propio estilo particular.

He is said to have influenced a whole generation of painters through his take on life and paintings, one such painter is Damien Hirst, who has also dealt with death – in his own particular style.